What is Spot a Shark?

Spot a Shark is a community-science program collecting photos of Grey Nurse Sharks from divers interacting with the sharks along the East Coast of Australia. These photos are used to support vital research, raise awareness and increase conservation efforts to protect this shark species.

For each shark photograph, the Spot a Shark team perform spot mapping techniques and use sophisticated software (hosted by Sharkbook) to determine which individual shark was sighted.

Identifying individual Grey Nurse sharks helps track shark movement, monitor overall health of the population, and help monitor behaviour and changes at local aggregation sites over time. This information is used by Spot a Shark researchers, as well as international partners, to facilitate management decisions aimed towards conserving our Critically Endangered population of Grey Nurse sharks. By supporting this project, you are helping researchers gather valuable data, which may help provide long-term protection for the Grey Nurse sharks and their habitats.

Why we do this?

“Extinction is imminent in the East Australia population without urgent conservation methods. Our East Coast population migrates between NSW and QLD and their distinct DNA structure suggests that they have been separated from other Grey Nurse (or Sand Tiger) populations for many thousands of years. The only hope for this population of sharks is to protect and conserve at is left of this fragile population. Targeted over-fishing to these sharks decimated the population in the 1970s leaving only around 200 individuals left. Spot a Shark aims to raise awareness and gather evidence to help protect this shark species so that future generations can continue to marvel at their outstanding beauty”, Sean Barker

How does it work?

1. Photograph a shark

Every shark has a unique spot pattern on each flank. A photo of either the left of shark, or right of shark can be matched to another photo of the same shark, or your shark may be a new addition to our database.

2. Submit a photo

You can upload files from your computer, or take them directly from your Flickr or Facebook account. Be sure to enter when and where you saw the shark and add any other information where possible, such as flank, sex and whether it was hooked or scarred. You will receive email updates when your shark is processed by a researcher or matched in the future.

3. Researcher Verification

When you submit a shark identification photo, a local researcher receives a notification.

This researcher will double-check the information you have submitted. After this, your photo is available for match searches. Please be patient as it may take a few days.

4. Matching Process

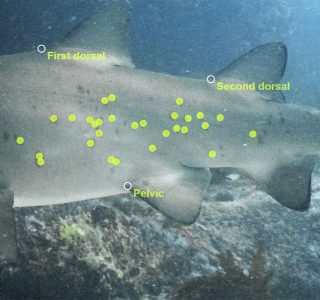

Once a researcher is happy with all the data accompanying the identification photo, they will spot map the shark and run the matcher algorithm.

Using algorithms designed by NASA for stargazing, the unique pattern of the shark will be compared with thousands of other photos The algorithm is like facial recognition software for shark flanks.

5. Shark Match Result

The algorithm provides researchers with a ranked selection of possible shark matches. Researchers will then visually confirm a match to an existing shark in the database, or create a new shark profile. At this stage, you will receive an update email and if the shark is new you have an opportunity to provide it with a nickname!!

About the species

- Scientific Name: Carcharias taurus

- Life Expectancy: 17~25years (max ~35years if not hooked).

- Biology: Ovoviviparous (young hatch inside). They have 2 uterus, with the young eating each other until birth, when only two pups will be born (one per uterus).

- Sexual Reproduction: Females sexually active from between 9-10 years old. Only breed once every 2 years with a 9-12months pregnancy term.

- Diet: Small fish, rays, crustaceans

The east coast population is critically endangered in Australia. This population is genetically distinct from other populations. They have one of the lowers reproduction rates among sharks, have a small population, are vulnerable to recreational line-fishing and commercial fishing, and vulnerable to the Shark Control program’s shark nets and drumlines. Their biggest threat is ingesting fishing hooks which can puncture their internal organs and cause slow death. Replenishment of the critically endangered eastern Australian population is unlikely to be achieved via natural migration due to distances from other populations.